Mountains and diversity: why are there so many lizard species in the Caucasus?

Were Charles Darwin and Ernst Mayr correct? A recent study of a diverse lizard genus suggests they were.

Charles Darwin first wrote that geographic isolation is an essential precondition of natural selection; he exemplified the pattern with famous Galapagos finches. He supposed that the one finch species had once expanded through the islands of the archipelago, and natural selection acting against various environmental conditions caused the emergence of multiple finch species differing in color and shape of the beak.

One of the most prominent evolutionary biologists of the XX Century, Ernst Mayr, expanded this idea: what happens after species, which emerged in isolation from a common ancestor, meet again? Well… If they did not have time to develop sufficient differences, they could freely interbreed and eventually merge again into a single species. However, if the differences are strong enough, the viability of hybrids will be lower than that of non-hybrid individuals. Natural selection then supports the characters that prevent hybridization. Those can include behavior, coloration, size, or any other peculiarity that forces the individuals to prefer their conspecifics as mates and to ignore potential mates of closely related species.

It is a simple, albeit not universal way of speciation. Multiple genetic studies show that some major changes affecting the reproductive system can emerge even without isolation, and this can be a pathway to the development of new species in the same geographic space. But how common is “traditional” speciation through geographic isolation, and does it really dominate?

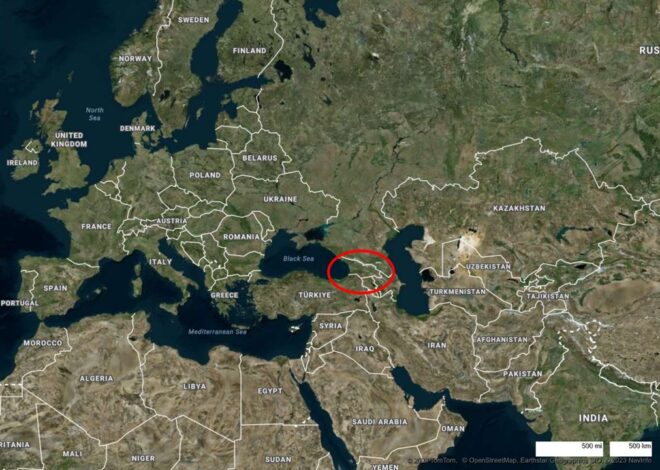

A recent study of spatial divergence of an interesting group of Caucasian rock lizards from the genus Darevskia supports the universal applicability of the “traditional” speciation pattern. These lizards are unexpectedly diverse for non-tropical vertebrates. The limited space between the Black and Caspian seas hosts over 30 described species of rock lizards, among those – seven parthenogenetic species, which have no males and reproduce as natural, all-female clones. Such diverse animal groups are not rare in the tropics; however, for the mountainous region with a temperate climate, the diversity of rock lizards is really high. So, how could such diversity emerge, and whether secondary contact between the emerging species plays a critical role?

In a recent paper published in the Biological Journal of Linnean Society, scientists from the Institute of Ecology of Ilia State University compared about 250 geographic locations of 11 species of lizards. The evolutionary relations of these lizards were established earlier. Some of these species had broadly overlapping distributions; the ranges of the others are located closely but do not overlap (biologists call it “parapatric distribution”). Some species live in the same broader geographic area but never occur in the same place: they may live at different altitudes within the same mountain valley.

When the overlap of the ranges was compared with their genetic closeness of the species, it appeared that only the lizards that had been separated from a common ancestor over 5 million years ago may have lived in the same location. Those with shorter divergence times live in the same geographic areas, but their locations never overlap. Finally, the lizards that were separated “only” a few tens of thousands of years ago never occur in the same geographic space.

Mutual avoidance of the related species may be more or less effective and based on the more or less complicated mechanisms. The easiest way is just not to live in the same geographic space. In this case, contact between animals that belong to different species is rare, and it is unnecessary to have complex behavioral or ecological mechanisms to avoid hybridization. Those who live in the same area but in different locations contact more commonly; hence, they need to develop at least some mechanisms of potential mate recognition which prevent too common hybridization.

Finally, less related species commonly occupy shared locations. They differ enough to make common hybridization impossible. They may have very different body sizes or various coloration or are active at different times of the year. As a result, up to four lizard species are found on the same rock simultaneously.

As a result, a diverse rock lizard fauna emerged in the Caucasus Mountains. Some have relatively large bodies, while others are very tiny. Their belly color varies from brick-red to white; spots on the back are irregularly positioned or very symmetric. Some are stuck to the rocks, others dwell in the forest litter. This diversity makes the rock lizards an important and sustainable component of the ecosystems: in case of extinction of one population, another species overtakes its ecological function.

As we see, huge progress in research techniques does not change many seemingly old and outdated concepts. Indeed, reading books by Ernst Mayr and Darwin’s “Origin of Species” makes sense not only for those who are interested in the history of science.

Go to the link:

Related Posts

Lice that don’t bite

“Who Cares?: World’s Best Mothers”