Sex and Reproduction: Why Do Males Exist?

We know that there must be individuals of two sexes for successful reproduction. However, this is by no means a universal rule. So why did nature create sexual reproduction?

Reproduction in nature is associated with mating of individuals of two sexes. Mammals, birds, reptiles, fish, insects, and spiders have males that fertilize females of the same species, and as a result, a new organism starts developing. Even in plants, there are “male” and “female” reproductive cells: pollen and seeds. However, this is not a universal rule. Many living organisms have the ability to reproduce without mating: the female produces an egg that can develop into a new organism, again a female, which is, effectively, a genetic clone of its mother. The most of the lower animals may, at least occasionally, reproduce in this way, although in complex animals, including as insects and vertebrates, asexual reproduction is rare.

So why fertilization process is needed? In fact, sexual reproduction is quite expensive. The presence of males requires additional resources – food and space, which are often in short supply and lead to competition between individuals. In short, animals that reproduce sexually need twice as many resources as animals that reproduce asexually for producing the same number of offspring. However, asexual organisms have one significant drawback: their offspring are genetically homogeneous since they do not contain the genes of two parents in different combinations. Therefore, if the environmental conditions worsen, natural selection is powerless to save even particularly well-adapted animals: almost all will die. As a result, virtually all living organisms, even bacteria, maintain the ability to exchange, at least occasionally, genetic material between the individuals. The only animal believed to have completely lost the ability to reproduce sexually was the primitive aquatic organisms, rotifers; However, just three years ago, scientists discovered that their genes also recombine. Hence, sexual reproduction also occurs in rotifers, albeit rarely.

Considering this logic and facts, the optimal survival strategy for any living organism is to alternate between sexual and asexual reproduction. In asexual reproduction, organisms reproduce rapidly using fewer resources and reach high abundances; when gene recombination replaces asexual reproduction, their gene pool is diversified, allowing them to better adapt to changing conditions. Such alternation is typical for many invertebrates, including small crustaceans – water fleas and copepods, herbaceous plants, which alternate reproduction by seeds and by shoots, and many others. That is why it is strange that a substantial part of animal species – including insects, snails, most vertebrates, spiders, and many others, including all mammals – have lost the ability to reproduce asexually.

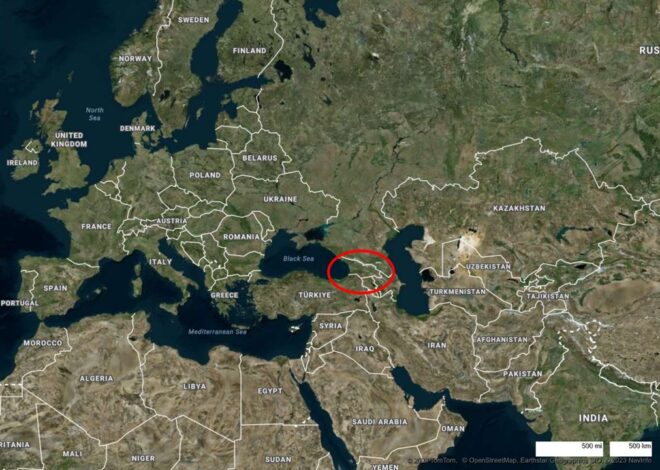

However, rarely, asexual reproduction also occurs in vertebrates. For example, there are several genera of lizards where, as a result of interspecific mating, the hybrids have lost the ability to block the development of the egg before being fertilized; Once the egg is formed, it immediately starts to cleavage and forms into a developing embryo, which is a complete genetic copy of the mother. There are only a few such reptile groups worldwide; one of such groups of asexual lizards is the Caucasian rock lizards, which inhabit the Trialeti ridge and Javakheti plateau in Georgia.

For many years, scientists believed that these parthenogenic (asexual) lizards represent the “deadlock” of evolution: they can arise as a result of random hybridization, but they do not have a great future – they cannot adapt to environmental conditions, for example, climate changes, and are doomed; However, in the short term, these animals may outperform even their bisexual ancestors because they reproduce faster. In recent years, scientists have shown that it is a very simplistic view of the evolutionary perspective of asexual lizards. In 2017, the research group of Ilia University published an article showing that two species of asexual lizards living in Georgia are genetically related. It turns out that asexual lizards occasionally mate with males of a related sexual species. These occasional matings were already known, but zoologists believed that, as a result of these matings, it is impossible to give birth to a fertile offspring. Research on genetic markers has confirmed that this is possible indded. Moreover, fertilization of an asexual lizard by a male can, in exceptional cases, create a new asexual form! Thus, one of the asexual species living in Georgia, it turns out, developed as a result of the fertilization of another asexual species.

In the following years, the genetic research of all seven species of asexual lizards was carried out by an international team of scientists. Any pair of asexual forms appeared to be identical in at least one genetic marker, and one can hypothesize that a hybrid, which once switched to asexual breeding, in the course of subsequent matings, has produced these seven distinct asexual species, having different ranges and adapted to various ecological conditions. These parthenogens reproduce rapidly, and are successful, considering that they occasionally “create” asexual species adapted to new habitats, and, in fact, can multiply and diversify endlessly.

Many studies of asexual organisms have shown that asexual reproduction did not develop once in the course of evolution. Different organisms developed sexual reproduction independently of each other and with involvement of different mechanisms and genes, and animals and other organisms that reproduced sexually independently of each other reverted to asexual reproduction. This issue remains one of most interesting and challenging problems of evolutionary biology. We hope that increasingly popular genomic methods will shed light on this issue. Now, for those who are more interested in the problem, we offer two links:

https://bmcecolevol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12862-020-01690-9

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2023.1184306/full